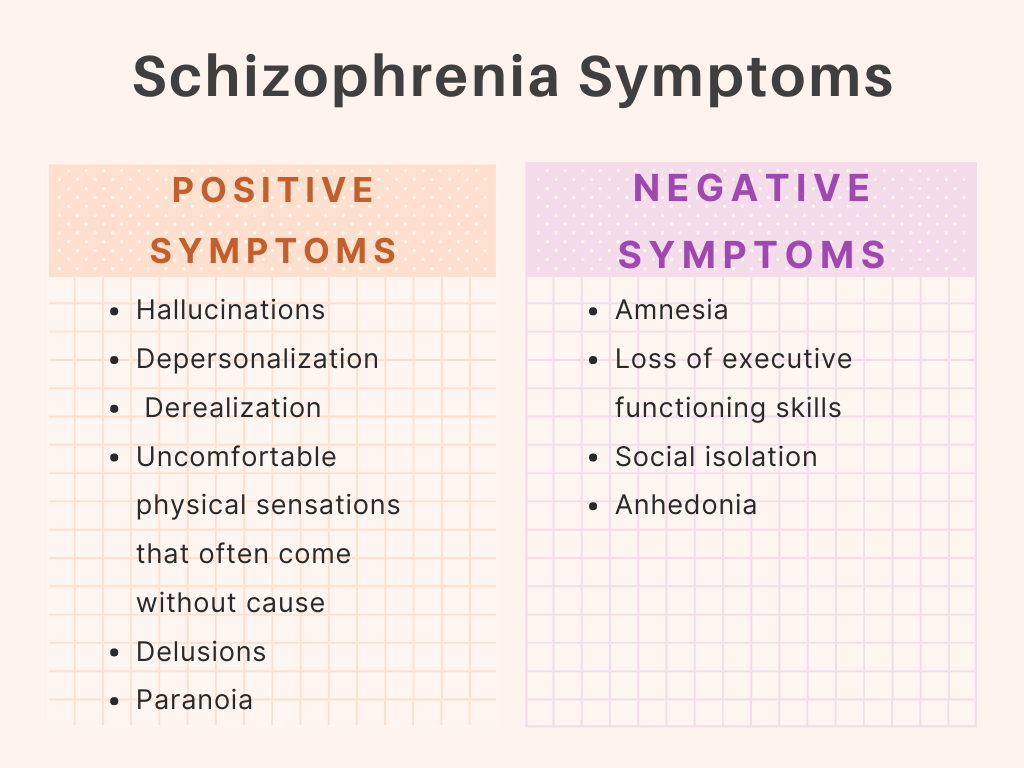

Schizophrenia is a complex mental illness that is usually only effectively treated with medication. It can be uncomfortable and scary, with symptoms that are generally characterized by a detachment from reality. Symptoms are divided into “positive” and “negative,” positive symptoms being thoughts or actions that are added to someone’s psyche and negative being normal thoughts or behaviors that are detracted.

Positive symptoms include hallucinations, depersonalization, and derealization, uncomfortable physical sensations that often come without cause, delusions, and paranoia. Negative symptoms include amnesia, loss of executive functioning skills, social isolation, and anhedonia. Experiencing these symptoms often leads people with schizophrenia to be wary, irritable, and fearful, which makes it difficult to connect with others and be comfortable with oneself.

For a long time, people with schizophrenia and schizophrenic symptoms were cast out of society and believed to be insane. They were considered heretics, witches, and criminals, shunned for displaying behaviors they couldn’t control that only worsened without treatment. Even now, people who are strange, twitchy, or any manner of other “abnormal” things are called “schizo” and sneered at in disgust, and those who disclose their schizophrenia to peers often find themselves treated with trepidation and fear, even by those they trust most.

However, having schizophrenia doesn’t make a person crazy or inherently more dangerous than others. When treated with a group of medicines called antipsychotics, those with the disorder can lead typical and fulfilling lives, too. Even without them, this is occasionally possible—for example, esteemed mathematician John Nash had severe schizophrenia, and while he was never properly treated for it, he went on to win the Nobel Prize in economic sciences and was so influential in his field that he inspired a famous movie called A Beautiful Mind.

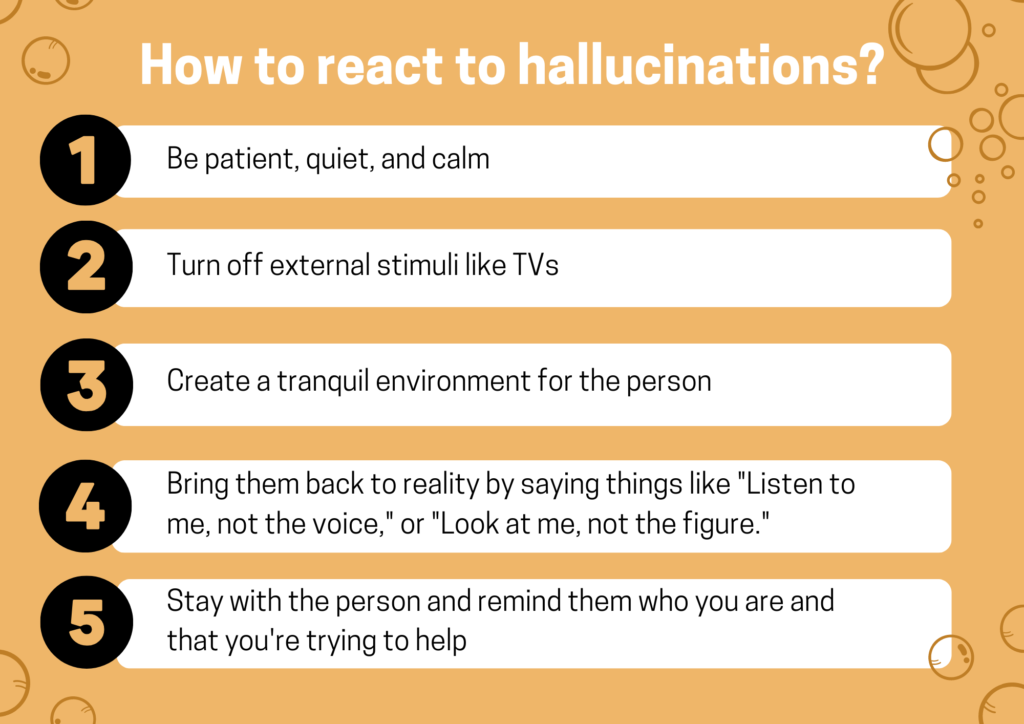

It’s true that watching someone experience schizophrenic symptoms can sometimes be as scary as experiencing them, especially when you care for the person. The good news is, there are ways to react to symptoms—since they can be hard, and even impossible, to control despite treatment—that make the experience easier for both parties. I’ll illustrate some of these below.

How to react to hallucinations (auditory, visual, tactile, etc): be patient, quiet, and calm. Turn off external stimuli like TVs and try to create a tranquil environment for the person. If they’re calm enough, let them know that you aren’t experiencing the hallucination, and ask them exactly what it is they’re experiencing. Then, try to bring them back to reality by saying things like “Listen to me, not the voice,” or “Look at me, not the figure.” Stay with the person and, if they seem dissociated or distant, remind them who you are and that you’re trying to help. Answer any questions they may ask. If they’re lucid enough, consider asking them what you can do to help, and act accordingly.

How to react to delusions: the most common type of schizophrenic delusions are what’s called paranoid delusions, which lead someone to believe that they’re going to be harmed or hurt in some way. This means that the person might be convinced of your own ill will, so it’s important to keep enough distance that you know you’re safe. Remind the person that they, too, are safe and that no one is going to harm them, but don’t be alarmed if your words don’t get through at first; delusions can be difficult to combat. Remember not to argue about or attack the person’s delusion, as this can be distressing. Never say things like “That’s ridiculous” or “What’s wrong with you,” but, like with hallucinations, try to gently ground the person back in reality.

How to react to erratic behavior: this is a vast category and can include things like irritability, paranoia, aggression, distrust, panic, and mania. Dealing with these behaviors will depend on which one(s) the person is exhibiting, but there are a few rules of thumb that are generally applicable. Most importantly, try to create a safe and calm space for both you and the person exhibiting symptoms. Understand that the person is not acting this way on purpose, and that they can’t help how they feel and even sometimes how they act. Ask questions about and validate the person’s feelings, but let them know that your experience is or isn’t contrary to what they’re telling you, particularly if they’re distressed or paranoid about something unlikely happening.

Like all mental illnesses, schizophrenia is complicated and can’t be fixed with a few well-meaning words. Unlike depression or anxiety, it isn’t rooted in beliefs that can be fixed with psychotherapy (like “I’m worthless” or “Everyone’s judging me”), so the best intervention for this typically lifelong disorder is regular therapy paired with medication. Only about one percent of the adult population has schizophrenia, but it’s still worth learning about. Its symptoms sometimes surface in other disorders, too, so the care originating for schizophrenic patients is often applicable elsewhere—this is why it’s so crucial to learn about and have compassion for people with mental health disorders, whether you’re going into the field or you’re just a well-meaning person who likes to be prepared for anything.

Author: Rose McCoy